SHEEP FARMING IN THE FAROE ISLANDS

JULY

I had dreamed of this place for a long time. Intrigued by the breathtaking landscape that had been carved out and shaped by the elements. Raw and enchanting. The cloud was low as the plane drew in, and I could see only snippets of black rock and blue water below. It had been a long night of travelling, but my energy levels were running high as the plane made its descent towards the small airport on the island of Vágar. I was due to meet with a local farmer called Jóhannus, who was going to be my contact throughout the duration of this trip. He runs his own business called Reika Adventures, where he specialises in guided trips and adventurous excursions. He has worked with the likes of Google, National Geographic, the BBC, and Netherlands based high-lining team, the Dreamwalkers. Like many of the islands’ inhabitants, he is many things: farmer, hunter, fisherman and engineer. He is also constructing a new build with his brother, Vilhelm, where they’ll keep sheep, sell food and other goods, and offer accommodation to tourists and locals.

Touchdown. I was out of the airport in no time, picking up my car and setting off for Gásadalur. This scenic village is home to only a dozen permanent residents, but its infamous waterfall, Múlafossur, brings thousands of tourists here every year. The day was almost perfectly clear, a high cloud leaving the mountains bare in the bright light of summer. Green grass grows everywhere, even on the roofs of houses, I noted, as I passed a small village that looked out over the famous sea stack of Drangarnir and the islet, Tindhólmur.

All feelings of fatigue left me as I neared the village of Gásadalur, and I felt a surge of excitement in the pit of my stomach. Upon entering the village, I spotted a sheepfold already full of sheep. A huge coach blocked my way in as its tourists disembarked to crowd around the pen, snapping photos of the farmers and their livestock. I pulled up, managing to catch the eye of a young farmer whom I hoped was Jóhannus. Introducing myself, I asked whether the tourists had permission to take photos, but he merely shrugged and said that they never even ask. The sun was rising high, turning from late morning to early afternoon, although it had already been a long day for the farmers, who’d been up at sunrise to herd the sheep down from the mountaintops.

The terrain in the Faroe Islands can be dangerous, especially with the unpredictability of the weather. It can change at any time and vary vastly from island to island. Loose ground falls away from your feet without warning, and a thick fog can descend within minutes to hide your surroundings completely. It’s the perfect environment for disaster, with steep cliffs that drop-down hundreds of feet into the open ocean. Only farmers and other locals will have the essential experience walking these mountains, and even then, they know when not to attempt it. There are no clear tracks or gravel paths like in many other places in Europe. Exploring these lands will separate you from everything else in the world; you can instead spend your time marvelling in the company of mother nature and her wildlife. With the country’s popularity growing every year, there are many guides that can take you hiking, with a range of different trips and excursions available on every island.

There are few fences to separate the land here, leaving the islands as untouched as possible. The sheep take advantage of this, and are free to roam across the valleys, high up in the mountains and even on the most vertical of cliff edges that drop straight down into the ocean. There’s an old tale that the Faroese sheep have longer legs on one side of their body because they spend most of their lives walking in such places. Herding them requires a lot of manpower, and without a sheepdog it can make the day’s work over 12 hours long, and you can bet there’ll be a lot more walking. In some areas, farmers have small islands where the rams (male sheep) get transported to and from via boat. It’s quite a task to ferry the livestock, but the quality of grass is very high, vivid green in colour, long and broad with a fresh smell. Mix this healthy diet with the rugged terrain to build strong muscles, and the rams grow quickly. When they’re weighed in the autumn, they’re sometimes double the size of an average ewe (female sheep), and their meat tastes very strong.

Herding takes place in July and August, weather permitting. Usually on a Saturday when people aren’t at work. Sundays are a day of rest, for church service and home cooking, and for time with the family. The summer months can be very labour intensive as there are many important tasks to carry out in preparation of the coming seasons; mainly, the shearing of the sheep. Their wool can be made into yarn, and in turn, made into traditional clothing or other gifts. Faroese jumpers are incredibly unique, most often made by the women of the family. They weave beautiful designs in a range of earthy colours, gifting them to family members for birthdays and Christmases. It’s not uncommon to see women knitting as they walk around, or as they sit in a café and talk with friends.

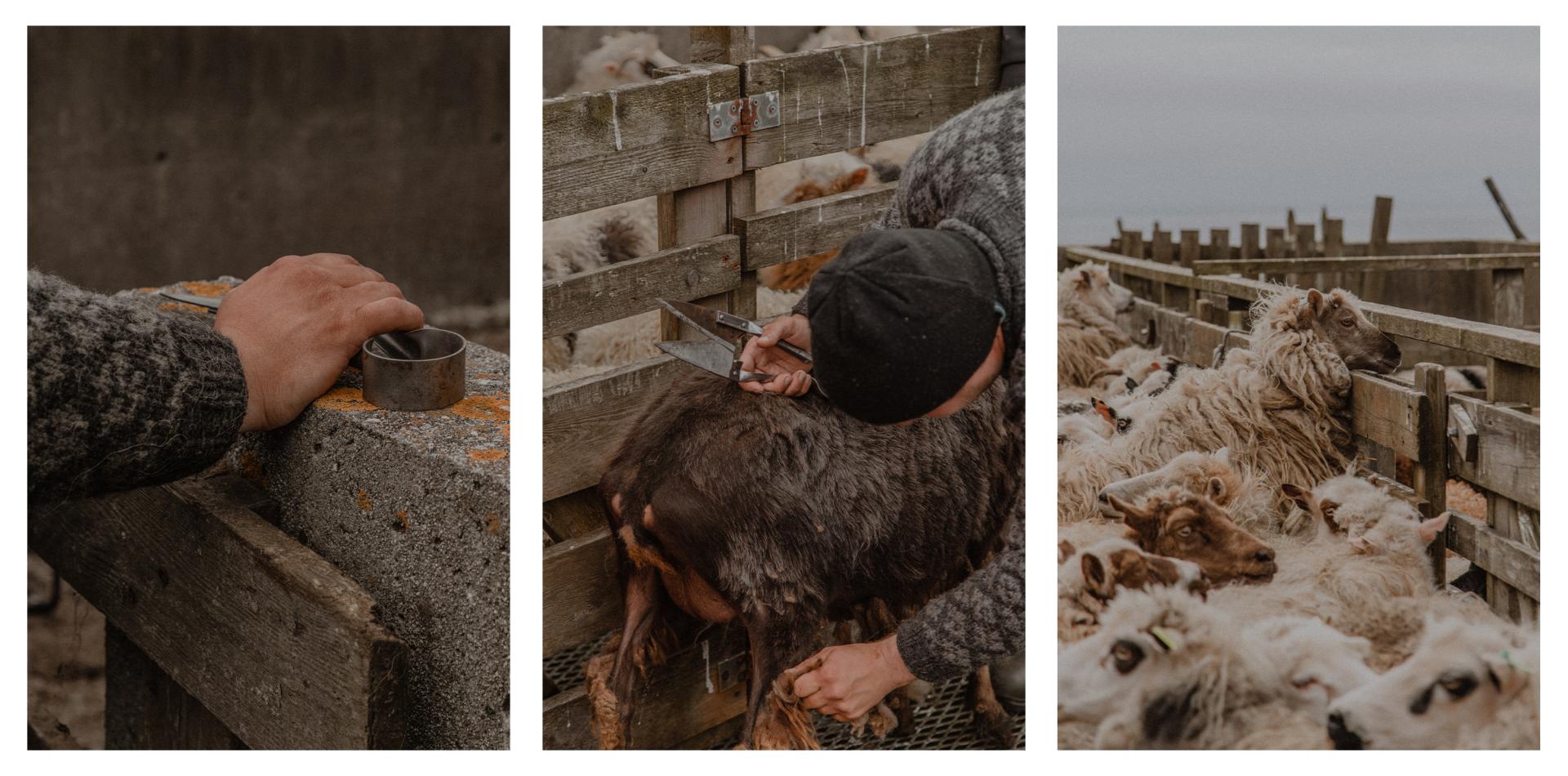

Once the sheep have been herded from the mountains, they are separated into different enclosures, grouping the lambs, ewes and rams into pens within the sheepfold. This was when I’d arrived, conveniently missing the hours of hiking in the mountains beforehand. Jóhannus reassured me that we would go herding another day, and that I hadn’t escaped that part of the job whilst I was here. I enjoyed the easy nature of the locals as they talked together, catching the flighty sheep and clipping them with traditional hand shears. It seemed to take a long time, with patches of wool sticking out all over their bodies as they wriggled around. Electric shearing is starting to emerge on the islands, with many foreign shearers flying in from all over the world. It’s an area of expertise that requires a lot of practice as to not injure the sheep, and although it takes less time and manpower than hand shearing, it’s still a very labour-intensive job. Many of the farmers I spoke to dislike electric shearing, as it’s very noisy, and you have the constant smell of petrol fumes. They also pointed out that a lot of the areas are so inaccessible that hand shearing is the only real option.

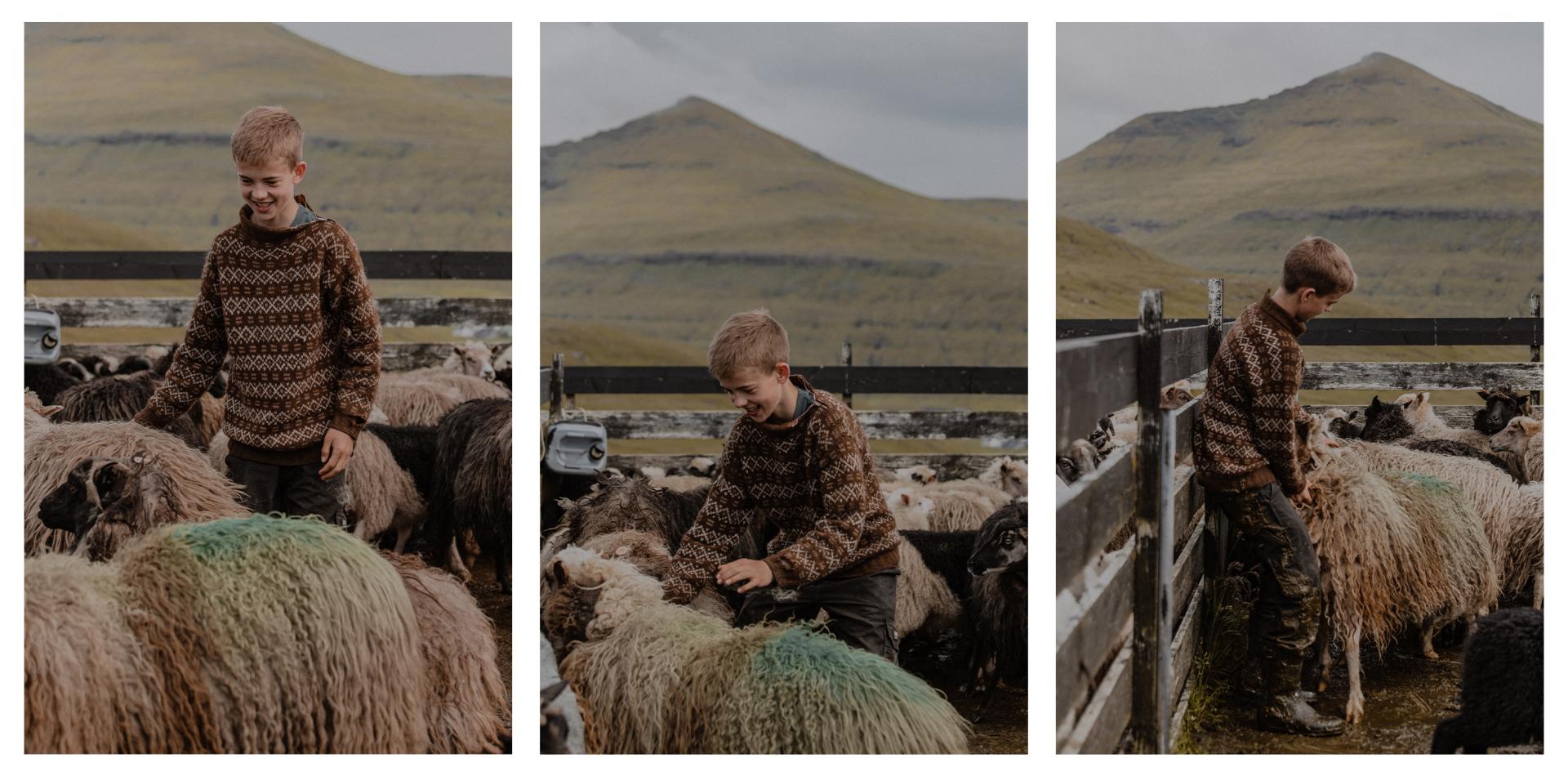

Shearing sheep seems to be a sort of family/social event here. Hours of talking and joking around, eating the traditional Faroese snack of skerpikjøt (dried fermented lamb) on buttered bread with some salt, and then some drinking as the day progressed. It is a male-dominated place, but they don’t discourage the women from joining in. Even children take part, some as young as toddlers, walking amongst the lambs, learning the way of island life at an early age. Sometimes in the afternoon, the farmers’ wives would visit, bearing gifts of delicious, warm pannukøka (pancakes) or vafla (waffles) with whipped cream and jam. However, it was too early in the day for food just yet, so I stationed myself on top of one of the sheep pens, straddling the fence with my cameras, ready to shoot on either side.

I could sense the unease of the animals; after roaming freely over the land for months, they were all penned up together, bleating a chorus of dissatisfaction. They normally graze over the highest points of the island in spring and summer, and slowly move downhill for food in autumn. Combine the fact that the soil here is notoriously bad for growing trees, crops and other provisions, with an average rainfall of 1387mm per year, and an average temperature of 6.7°C, there is never a guarantee that there will be enough grass to keep the sheep at a healthy weight all year round. This concern results in another essential task for the farmers to carry out during the summer. They must harvest the grass from their fields to store in drying sheds, which will provide the livestock with hay during the most barren months of the year.

The sheep waited, stomping impatiently for our day’s tasks to be done. There are over 70 different types of føroyskur seyður (Faroese Sheep) but they are all a breed of the Northern European Short-Tailed Sheep. These photogenic beauties have most likely frequented your Instagram explore tab at least once, and it’s not hard to understand why. Their wool is especially unique, in an amazing range of colours and patterns, with the rams boasting impressive horns too. Interestingly, some of the sheep naturally shed their coat. This, of course, made me ask why they had to be sheared, if it would come off naturally. Wool takes months, even years, to completely biodegrade; high winds can blow the loose fibres all over the islands and into the ocean. Seabirds may try to collect the wool for their nests, and it is known that they can become ensnared within it. In rare occasions, the wool can become so entangled around the bird’s body that they become too heavy to fly, or, it cuts off the circulation from their legs completely. This explains not only why shearing takes place, but also the importance of shepherds collecting any loose wool they find on their land.

A familiar accent penetrated my sub-conscious as I was taking down some notes, and I caught a Kiwi voice above the hum of the natives. Josh, a New Zealander, had flown across half the world to shear sheep in Cornwall throughout June and had just arrived to do the same in the Faroe Islands. Rather than spending winter in his homeland, he’d decided to offer his services in Europe, and much to his surprise, managed to score a job on one of the most rural places on Earth. You could tell from the ease of his routine that Josh had been doing this for a long time; oiling the down-shaft and comb of the handpiece, lining up the cutter precisely and resetting his counter before quickly donning his shearing shoes and trousers. The shearing lasted for hours, until the hot tea and biscuits that had been regularly passed around to keep morale high, had run out. We even got to try the traditional skerpikjøt, cut onto buttered bread and seasoned with salt, and DAMN, that was some strong meat on an otherwise empty stomach.

Another tour bus had pulled in and I watched as the same pattern from earlier began; silent tourists disembarked to stare at the scene before them, camera shutters clicking a few times before retreating back to the bus. I witnessed the lack of courtesy towards the islanders first-hand and wanted to know whether this was a common occurrence. Jóhannus explained to me that tourists are becoming an increasingly bigger concern to the locals, as many of them will take pictures through the windows of their homes, or even invite themselves in. This is especially common in a region called Reyni, which is located within the capital, Tórshavn. It is something that we travellers should be much more mindful of, as I’m sure we would not appreciate the same kind of behaviour in our own homes. Not to mention, throughout all of my time here, I never met a single local who was unkind. Instead, I’d find myself talking to them for a while and sometimes get invited back to their home for coffee and cake. Their hospitality is beyond what I’ve ever experienced in my own country. Similarly to Josh, I felt at home here straight away, and the culture of kindness is the main thing that makes me want to keep going back.

After plucking up the courage to try and catch a sheep, the farmers would laugh at my failed attempts, which only made me more determined. The shearing was coming to an end, with over a hundred sheep looking fresh with their new haircuts. The work was hard and required a lot of strength, and I watched as beads of sweat trickled down Josh’s face. The task of pulling over the sheep, shearing them carefully to avoid cutting the skin at their prominent hip and back bones, then cutting away any loose ends from when the animal had been wriggling around was tedious. Keeping it still was a task in itself, and I was definitely afraid of being kicked by their hard hooves.

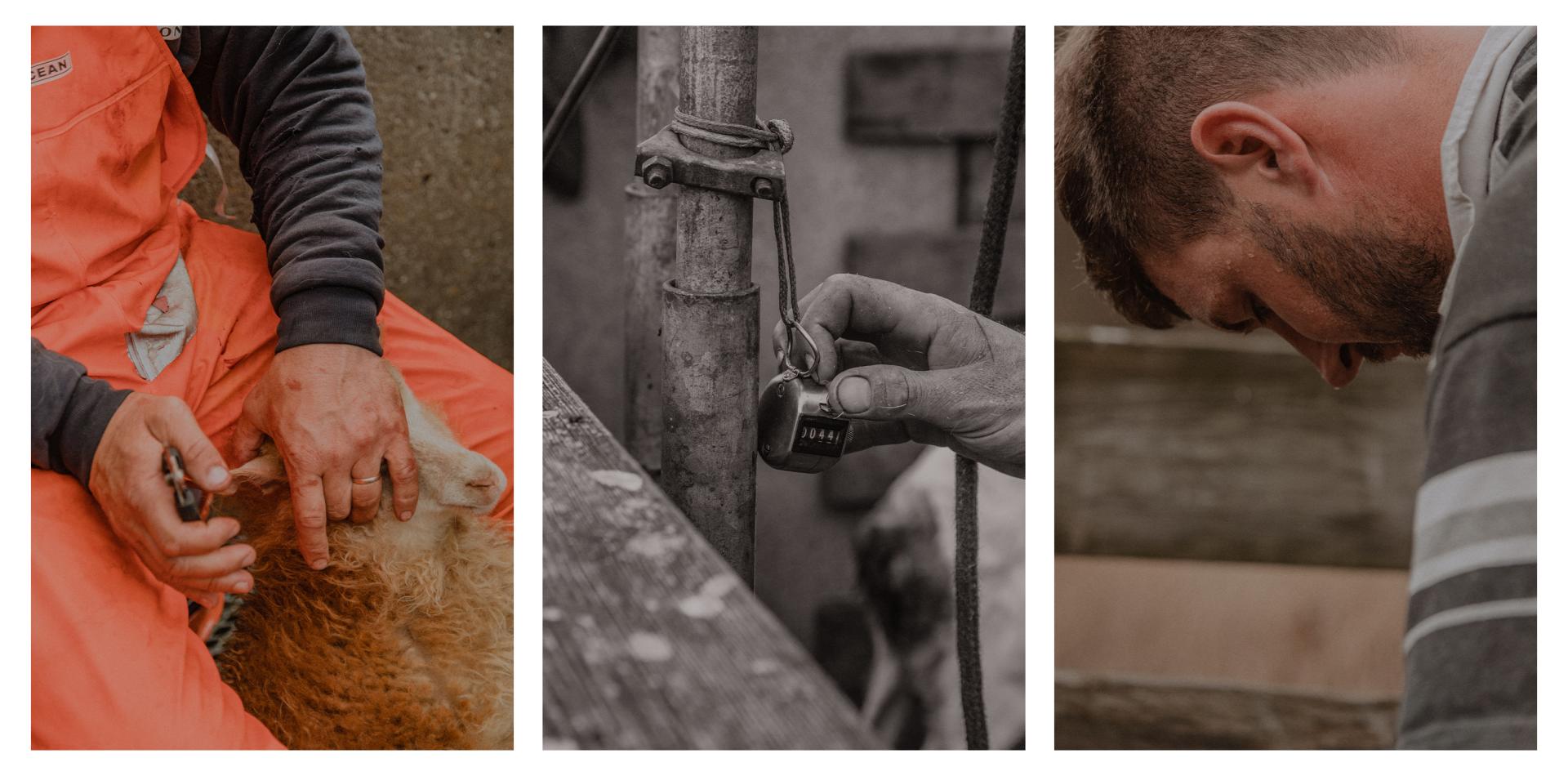

“Health checks” were also given, to see if the ewes were still producing milk, or to see if they had mjólkafepur (milk fever). Sometimes a hard lump would be found in their breast, which indicated the sheep might have cancer. When this happens, their number is marked down so they can be killed in the autumn, preventing a long and painful death in the mountains. The check is also done for another reason; to see if the lambs have been weaned off milk and are onto a grass-based diet instead. Due to all the lambing happening naturally in the mountains, the farmers have no accurate way of seeing how old their lambs are. Some are still very small in size and others have tiny horns sprouting from their heads. This is an exciting stage, because the farmers will find out, for the first time, how many lambs they have for the year.

The lambs’ teeth are checked, and they are administered worming medication, vitamins, minerals and other medicines. However, each area will carry out a different procedure; some areas will administer all of the above or only a few, and some areas will do none. There are many illnesses considered lethal for the livestock, and there is even concern when the lambs are brought down onto a different area. Their stomachs can be sensitive to a dramatic change in the quality of grass. After only eating the low-quality grass from the mountains, eating a high-quality grass from the valley can lead to an illness called skræpa, which causes diarrhoea, loss of fluids and, ultimately, death. All measures to prevent premature death or illness are taken seriously, and out of all the places I visited, I always saw medication being given. After all of this is completed, the lambs’ ears are cut. Each area has different ear markings. If the livestock wanders on a different patch of land, the farmers know where it came from and can return it.

Throughout the day, the air had been filled with the sounds of bleating sheep and electric shears, but Jóhannus insisted the sheep would only get louder once they’d been released. We were wrapping up for the day, with the counter sitting at 124, when I was told to get ready for the big moment. I hurried out across the field so the animals would be running towards me and I could get some pictures of the sheep reuniting with their babies. The sound of oyster catchers kept me company whilst I waited for the gate to be pulled aside. They called out, just like the sheep, as they flew across the sky and landed on a wall nearby. In my head, Chariots of Fire was playing, the sheep running over the mounds in slow motion until they got closer and the sound of them filled my ears. Jóhannus hadn’t been exaggerating; they were loud. A laugh escaped my lips and I felt a sense of freedom that perhaps the sheep were feeling too. I stood for a while, simply watching as mother and child found each other amidst the chaos. It had been a long day, but what an introduction it had been. I’d felt so welcomed and couldn’t wait to see what the following days would bring.

It was my final day in the Faroe Islands, and I didn’t want to leave. I really didn’t want to leave. I considered how likely it would be for me to become a sheep farmer, living my life out on these small islands in the middle of the North Atlantic. Today, we were going herding at another local farm, and we were going to cut the wool off every sheep by hand. I knew what to expect by now, instilled with more confidence and self-belief after trying many of the tasks that had been thrown at me throughout the duration of this trip. Arriving with Jóhannus, he introduced me to the farmers who we’d spend the day with. It was going to be an easy start, with four sheepdogs to make light work of the herding.

Opening up sections of the fence, we waited patiently for the sheep to start filtering through. High-pitched whistles commanded the sheepdogs, telling them to bear left or right, or to approach slowly from behind. Three of us were spread out on the bank opposite, to act as a deterrent for the sheep, who avoided us as planned and allowed themselves to be steered by the dogs. One of the things I had noticed about sheep was that they had a sort of panic button which could be triggered for no apparent reason. If one of the sheep became startled, it then startled the other sheep nearby, causing them to run and scatter with no real plan or sense of direction. It had been going so well, until that exact thing happened, and they ran off. Jóhannus sprinted uphill, waving his arms around to try get them back on course.

We’d managed to gather most of the flock, but a group of almost a dozen lingered in a dip by the stream. Three dogs and a couple of farmers made a horseshoe shape around them, trying to bring them up in the right direction. The sheep were getting closer and things were looking hopeful, but suddenly, they bolted upwards and around, escaping this year’s shear.

The main flock had already been separated into pens and shears were being passed around as we joined the rest of the group. Metal tables were carried in and would be used to keep the sheep still whilst we cut the wool. It was much easier to pair up and take a side each, and conversation quickly filled the air, like it had at Gásadalur. Although, this particular group of farmers were really good friends, and had spent many nights drinking, talking, hunting and hiking together over the years. Laughter erupted every few minutes, and I smiled at the ease of the atmosphere. Something warm touched my leg, and I realised I was being peed on by a sheep. Arnjohn and Jóhannus laughed at me, and I couldn’t stop myself from joining in. Medicine was distributed amongst the sheep, and beer amongst the shepherds as the day went on, smoothly. We all roared with laughter as Regin, the son of one of the farmers, tried to grab a sheep and got dragged across the floor, his trouser leg covered with excrement.

Waffles, jam and fresh whipped cream arrived, courtesy of Jona, and we all had a short break to fill our stomachs. Hand cramp was becoming a real struggle, and I was joined by two of the young sons, all of us cutting one sheep together. The lambs’ ears were cut, ewes checked, and the final snips were being made. It had been a long day, and all of us were looking forward to a good meal. Jona had been preparing a traditional Faroese dish called røst súpan (fermented ram soup) with carrots, turnip and meatballs, served with bread and boiled potatoes. By now, the men had had a lot to drink and were in high spirits, singing loudly at the table.

I returned to my accommodation, talking with my wonderful hosts, Thurid and Jógvan, about the day. They’d both become a sort of adopted family, and I was grateful for their home cooking and hospitality. I knew I’d be back to see them in October for the slaughter season, so I bid them a fond farewell, before catching my plane back home.

OCTOBER

October arrived and the slaughter season was already well underway. September had brought a wave of unusually good weather, which resulted in the season starting earlier than normal. The lambs were around six months old by now, fattened up on green grass, fresh water and lots of exercise. Jóhannus’ family had taken in two orphaned lambs during the summer, Trilla and Norðan, and we’d spent many days bottle-feeding them, laughing as they jumped, skipped and played around. I knew they were going to be slaughtered in the autumn, and it did make me feel sad because they would nibble our hands and face affectionately and let us stroke them. Trilla was especially well humanised. She’d even stand on top of the counter in the kitchen whilst being petted like a dog. Vilhelm explained that it is harder to kill the lambs when they raise them themselves because they develop a personal bond, but orphaned lambs are not uncommon, and there can be dozens across the islands every year. The average natural lifespan of a sheep is between 10-12 years, and when the islanders rely almost solely on lamb for their source of food, they can’t afford to keep dozens as pets because of a personal attachment.

Similarly to July, the first task was to herd all of the sheep down from the mountains and into the sheepfolds. We were up well before sunrise, getting ready for the day ahead, packing food and waterproofs before starting our ascent in blue hour. There are no paths or tracks to follow. You simply walk up, and by “up,” I mean almost vertically up, legs aching and lungs desperate for air. The locals cruised on as if they were out for a relaxing stroll, talking animatedly without missing a breath. We were surrounded by nature’s beauty, with panoramic views overlooking a fjord and out across the next island. I could see the golden light of sunrise starting to peak out from the clouds and I had to pause for a second to take in the view, completely speechless and awestruck. I glanced behind me to see where the herders were and saw them as small dots a good 300m ahead of me. Picking up the pace, I charged on, determined to try and catch them up. Hopping over a small fence, I walked in a line towards the nearest local, who was a farmer called Arni. We talked for a while before I spotted a familiar face coming towards me, Jóhannus from the trip in July. He introduced me to Levi, his brother-in-law and ex-footballer, before they both carried on uphill towards the peak of the mountain.

Shortly after, we were off at a brisk walk again, driving the sheep down and into the pens. It took another hour or so, having safely made it across the many streams, dips and hollows of the hillside. Lambs, rams and ewes were all separated into different enclosures, and number tags were placed around their heads so we could identify them easily. A metal scale had been rolled in, a sort of cage that would tell us how heavy the sheep were. The lambs were first, marking down their number and weight on a sheet of paper. Not all 178 of them would be slaughtered, as there had to be enough for breeding the following year. Seven male lambs were chosen for future mating, and to introduce new blood into the gene-pool. Ram is considered a delicacy, but the heaviest ram, which weighed a massive 91kg, would be used for mating rather than killed for food.

There must have been two dozen people there, everyone helping with the work. There were also a lot of kids joining in with their parents, holding the sheep or just watching from the walls. I felt such a huge sense of the community and culture, and a wave of respect for the islanders became rooted within me. A lot of the lifestyle in the Faroe Islands is considered as ‘brutal’, but I reminded myself that the life I am accustomed to is much less hands on, and infinitely more sheltered. A lot of us who reside in highly populated, developed countries, only see the final product of food in supermarkets. The locals in the Faroe Islands are familiar with the whole process, from the mating of the sheep to the consumption of the meat. The Faroese are not keen producers of waste, and you will find that all parts of the animal will be consumed here, even the head. I know of a jewellery maker called Alia Gurli who makes a range of beautiful rings, necklaces and earrings from sheep horn. Regardless of our personal diets, using every part of the animal seems like a healthy practice.

Jóhannus, Levi and Vilhelm had the difficult task of separating the list of livestock into 8 groups of an equal weight. It took a while, everyone ate lunch and continued with their own tasks. Some of the sheep that had been missed in the summer were getting their wool cut, and a lot of the sheep were getting some sort of medication again. I was busy eating the pannukøka that Thurid had made for me when they announced that they were finally done. The paper was cut into 8 strips and the sorting began. It wasn’t long until the groups were separated, and the farmers were loading the lambs up into their DIY trailers. The air was growing colder every hour, the blue of sunset now lingering in the sky. The final task of the day was to feed the lambs hay, so their stomachs didn’t get upset from the sudden change in grass. We agreed to meet within the next couple of days to begin the slaughter, where I’d be able to watch and learn how it all happened.

The lambs are killed using a sheep gun, then their throats are cut to bleed out. The blood can be collected in a bowl and whisked to prevent it from clotting. Much like pigs’ blood, which can be used to make black pudding, sheep blood can be used for food, too. The most traditional recipe is blóðpannukøkur (blood pancakes), made with raisins, flour and salted tallow, which we ate later that night.

The carcass is skinned with extreme care to ensure the meat is not contaminated by the wool. The sheepskin itself can be preserved and treated for use as a beautiful, decorative rug. The fat that surrounds the stomach is called netja and is very pretty when held up due to its unusual pattern. Jóhannus told me how the Sami people used to wrap netja around cuts of reindeer, so when they fried it, the fat would melt into the meat. The stomach is removed and placed into a large bowl, its contents are discarded, and the stomach cleaned thoroughly so it can be used in food. The fat around the small intestine is hosed through, fermented, and melted down to create a traditional soup base. The heart, liver and kidneys are also consumed.

When the process is finished, the carcass is weighed and tagged, and left to hang in the slaughter room for a few days so fermentation can begin. It’ll later be moved into the drying shed, where it can stay for days, weeks, months and even years. The sheep that are slaughtered must last until the slaughter season the following year, in time for the process to start again.